The Infinite Library

Haris Epaminonda interviewed by Christopher Marinos

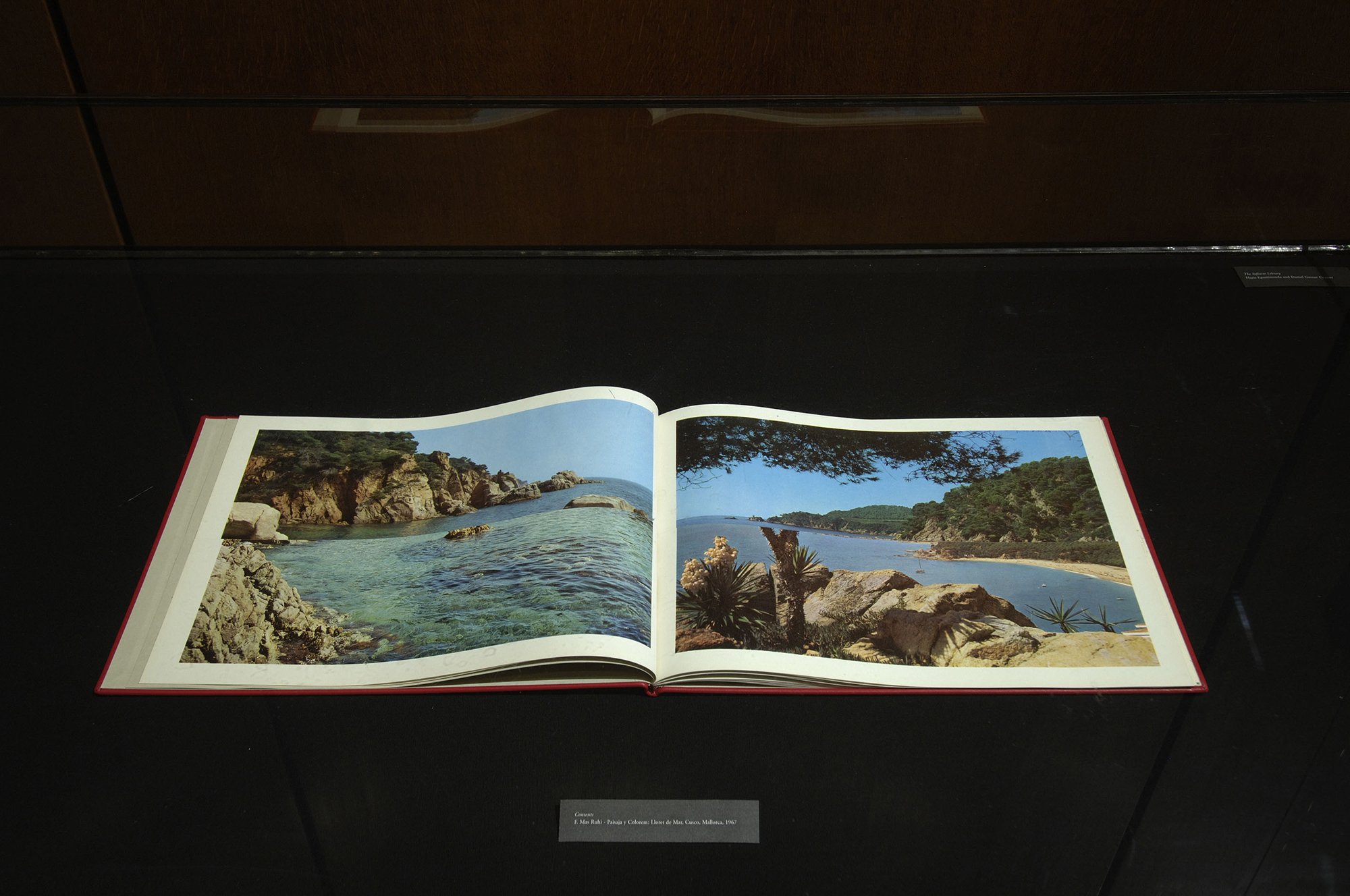

⁰¹ Daniel Gustav Cramer & Haris Epaminonda, The Infinite Library (Book #13), part of Untitled, installation at the Neue Nationalgalerie, 5th Berlin Biennale, 2007–08. Photo: Uwe Walter.

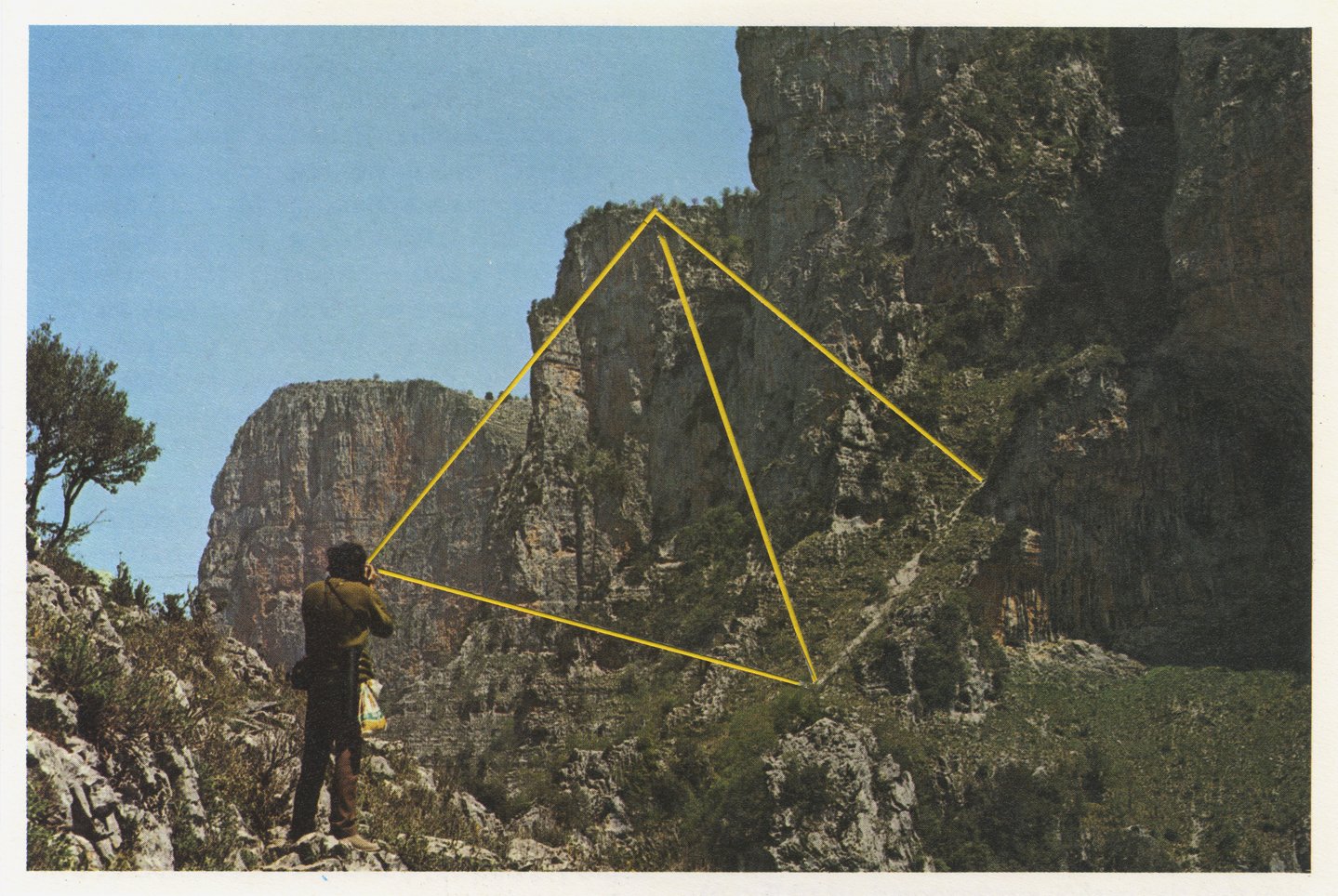

⁰²⁻⁰³ Haris Epaminonda, Untitled, series of collages and other works, paper, mixed media, dimensions variable, installation at the Neue Nationalgalerie, 5th Berlin Biennale, 2007–08. Photo: Uwe Walter.

⁰⁴ Haris Epaminonda, Untitled 009c/g, 2007, paper collage, 17.5 × 11.7 cm

Christopher Marinos: Could you tell me about your work The Infinite Library, recently shown at the 5th Berlin Biennial as part of your Untitled installation at the Neue Nationalgalerie? At first sight, it looks as if you pay homage not only to Marcel Broodthaers but, interestingly enough, to Ceryth Wyn Evans, who in the past has made work referencing Broodthaers’ 1975 Decor exhibition at the ICA in London.

Haris Epaminonda: The Infinite Library is an ongoing project in collaboration with Daniel Gustav Cramer. It was founded in 2007. It is primarily an expanding archive of books that result after dismantling and rearranging found picture books. Each book is created out of pages of one or more books and then bound anew. Several propositions applied to the project are kept as hypothetical text pieces, diagrams, drawings and sketches. The project is recently expanding into the realm of film, photography and installation. At the 5th Berlin Biennial some of the books were presented inside Mies van der Rohe’s glass vitrines alongside the collages and found objects, plants and the fish tank reflecting in effect the glass panels that defined the edges of the installational space and in their turn referring back to Mies van der Rohe’s architecture. There was no intention such as paying homage to Marcel Broodthaers or Ceryth Wyn Evans though there are obvious associations and connections.

CM: Did you have any particular model in mind when you first developed the idea for this project? I mean there are also obvious associations with Jorge Luis Borges’s writings on the infinite Library of Babel, for example.

HE: The project really took off while experimenting with books. We have been collecting many books which are by now enough to build a small hut. Not really having an idea of how to go about it, we started with this simple task of taking two books apart and later on putting them together anew and so from there we developed more ideas and ways of how the project could be built up. Really, more out of a gut feeling. Each book created is in a way an arbitrary system with its own logic. Like with all Borges’ writings, The Total Library, The Library of Babel and the Book of Sand are, and have been, a major influence. In his first short story in the Book of Sand, he writes about himself being an old man and his encounter with a younger person with whom he starts a conversation until he realises that this person is, in fact, himself several years back. The last story in the book refers to the actual Book of Sand which is the ultimate infinite book — which you can never read its pages twice because the content changes constantly. Of course there are plenty of valuable sources of texts and studies from writers, scientists, historians and philosophers who wrote on the notion of infinity, the universe, on libraries, books, etc. which we are looking at. Another kind of ‘image’ for The Infinite Library that just comes to my mind could be the ‘ocean’ in Stanislaw Lem’s Solaris, in which, while the scientists succeed in finding out the purpose and reason of the ocean’s behaviour, they fail to understand any motivation or meaning. What makes it an interesting project for us is that The Infinite Library is somehow self-referential, which means that it does not necessarily try to convey a meaning that refers to the outer world but to itself which could be seen from a certain perspective as an analogy of the world.

CM: In one of the most thorough reviews of the 5th Berlin Biennial, art historian André Rottmann suggested that the show ‘offers ample opportunity to take stock of the currency of referentialism in contemporary art, an artistic model that integrates pointers to particular works of preceding generations of artists, a vast array of historical episodes, theoretical writings, or aesthetic codes outside the field of art proper.’ [i] How does your work relate to that? Do you feel comfortable with this interpretation?

HE: To describe a little bit how I came about making this work: initially I was allocated a space in the KW though later on the curators felt that the work would be best suited for the Neue Nationalgalerie. I was then given the area of the former cloakroom of the museum which was made of permanent, floor-standing wooden panels near the left front corner of the building. By constructing identical panels made of glass on the opposite side of the wooden panels, I thought I would create more of an intimate enclosed space but still allowing the sense of transparency (a dominant feature of the host building) to emanate through; dark floor material would also make the space seem more dense. In the meantime, I visited the museum time and again to get a feel for it. The more I got accustomed to it the more I understood the importance of this perfect example of late modernist architecture. You kind of feel as if you are underwater and that you are part of a microcosm because the building itself feels so big and ungraspable, the inside and outside being separated by a layer of a thick, see-through material but one that allows both exposure and isolation at the same time. I was convinced that I should include plants and a fish tank within the environment that had gun to take shape. The books, the statues and the collages all somewhat became the point of departure towards one another and if I would have to draw lines of connections, in the end I would see it as a big web of linear associations from one to the other, each referencing partly to its own process of becoming and partly to each other. I very much like the idea of creating spatial relationships between things, like it can happen with collages within the two-dimensional space, with installations — forming constellations — within the three-dimensionality of space or with video and film through a timeline. Back to your question though: I think it is important that with each work of art, what remains touches people and leaves a mark. There is nothing wrong with ‘referentialism’ in contemporary art as far as I am concerned. I think it is necessary to observe what it is that the work has to say, as it is perhaps not enough to ‘refer’ without at the same time the implosion of the ‘reference’. ‘Referentialism’ seems to be something that relates more to the external world, though that which can emerge from within can be much more compelling. What I mean is you got to have something to say other or more than the repetition or admiration to former artistic modes of expression, aesthetic codes or historical facts and writings. It is true that there is a current trend and it is one that may involve a certain risk to which a work can be overkilled by what was first its basis or driving force. But there are quite a few artists in my view who succeed in overcoming this and who use ‘reference’ as a means through which they can generate new insights and ways of seeing. I think the total construct of this year’s biennale, as A. Rottmann puts it, seems to be a reflection of what is at stake in art at this very moment but perhaps it is also an indication of that which is to follow.

CM: This obsession with referentialism makes Marcel Schwob’s idea of the ‘mime’ (as a short text composed of several other texts) extremely relevant today. Are your ‘constellations’ touching upon issues referring to the occult and/or to decadent literature and imagery?

HE: No, I guess not really any that I am aware of. To try to convey something without the use of words but through gestures or movements is, I find, very interesting. I like the idea of the mime, because it does not only reveal something about the ‘thing’ in question but also tells something about perception. It means that we can actually read the world by the gestures and movements that the world in return reflects back on us. When the wind blows and the leaves of a tree turn towards one direction, we know already that the wind comes from the opposite side. Images can do what the wind does. They can change your point of attention and become both the pointers and the points of reference from which one can contemplate on further. Often, while looking at images, we are left with a feeling of ‘vulnerability’ because we can feel the effect, the working of the image on us but we don’t necessarily see or understand why it has the effect it does or where this is really coming from. Consciousness also functions similarly, I think.

CM: Speaking of that function, with which artworks or pictures do you get this feeling of ‘vulnerability’? I reckon that Alain Resnais’s Last year at Marienbad must be a case in point, and an all-time favourite.

HE: I remember the exhibition of Raoul de Keyser at the Whitechapel gallery four years ago in London. It was such a powerful experience for me to see his paintings because though at first sight they seemed very quiet and understated, they slowly worked their way through me so that by the time I had left the gallery, I was so deeply moved that I decided to go back the same day and see it again. I still recall the feeling I had, it was very beautiful. Last year at Marienbad, is an incredible film as well. Another kind of journey through space and time, in this case the camera moves physically through inside and outside spaces, and the angles and perspectives constantly change so you have the sense that even the hotel, the people, the corridors, the garden, the statues and the pictures on the wall are mere signifiers of a dreamed world, where past, present and future are all intertwined. It is very interesting how the plot develops while the scenes keep shifting from and to different time zones.

CM: What was the starting point behind your video Nemesis 52, 2003? In many respects, that was a breakthrough work, since it launched a distinct aesthetic system of yours.

HE: I had this image in my head of a character that is dressed in some weird costume while undertaking several meaningless actions performed in parts, a kind of magic show or like a strange ritual without it making much sense overall and without one ever being able to see in full the person that initiates all movement and action. It all developed while filming.

CM: Your cerebral, elegant collages attest your sympathy for the now-forgotten: that is, for vintage books and old printing techniques. But how does that conform to the violent slashing of images and the tearing up of pages?

HE: I find much pleasure in taking something that already exists and changing it into something else or putting it into a new context. Cutting is one way of achieving that. But I get the same pleasure when I take photographs or when I make a video or film. Moving image works in similar ways, for example. After you have gathered the material, you can start editing/cutting, overlaying and restructuring the original footage/s to achieve the result you wish. I guess I like images of the past because of their aesthetic qualities; the colours, tones and textures, but also because I can have a distance from them.

[i] André Rottmann, “Review of the 5th Berlin Biennial”, ArtForum, Summer 2008. Also online at http://artforum.com/inprint/issue=200806&id=20397.