Revolution I Love You

Reviewed by Giorgos Giannakopoulos

As is well known, this year marked the 40th anniversary of the 1968 events, a numerical rounding off that caused a series of ephemeral ‘events’ throughout Europe and the rest of the world. A handful of people and institutions commemorated what has become known as the ‘68 legacy’ with projects and discussions that varied from personal reflections and narrations to collective events and expositions. Thus, once again, light was shed on an era that in many ways shaped our thinking of the ‘contemporary’. [i]

In Greece this commemorative aura took the shape of a multi-faceted interdisciplinary project that sought to bring together a diverse group of scientific and cultural discourses analysing crucial aspects of the ‘long sixties’. Indeed, the Days of ’68 revolved around a cinema festival, a contemporary art exhibition (hosted by the Centre of Contemporary art in Thessaloniki) and an international historical conference entitled The Utopian Years: 1968 and Beyond. Movement Dynamics and Theoretical Implications 40 Years Later. [ii]

The project aimed to contextualise and historicise the 1968 era so as to bring into light the diasporic global nature of ’68 and the multi-dimensional political and cultural articulations that have emerged since then. As historian Antonis Liakos noted, with regard to the above-mentioned historical conference organised by the journal Historein, what is needed nowadays is a thorough ‘research of the ways in which those days influenced the new social movements and collective subjects, the changing notions of culture and cultural practices, their impact on scientific terrains and the theoretical perspectives’ that were opened. [iii]

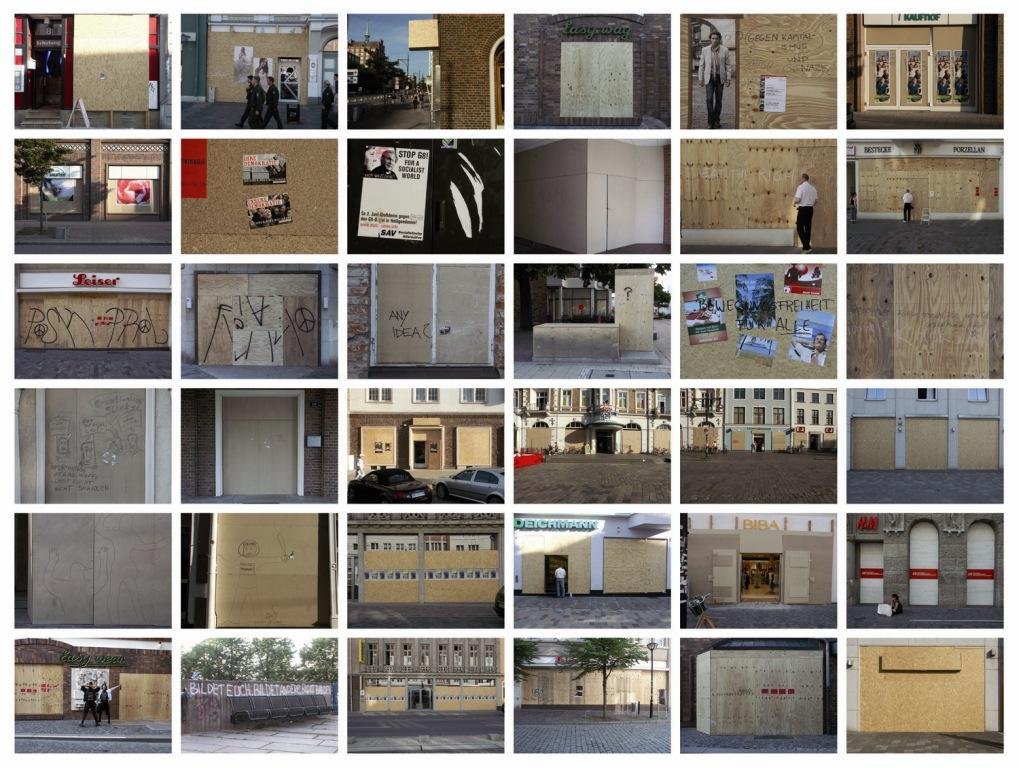

Moving from history and theory to contemporary art and curatorial practice, Revolution I Love You calls for, in Syrago Tsiaras’ words, an investigation of ‘the ways in which the desire for social change, as a practical realization of the dream of liberation on the individual and collective level, is given visual form in the works of artists from different geographical and cultural environments’. [iv] Hence, a small group of little more than a dozen artists that are active all across Europe, the US and Australia started this May, in Thessaloniki, a journey that will conclude in the International Project Space of Birmingham via Budapest and the Trafó Gallery, under the curatorial auspices of Maja and Reuben Fawkes. [v]

Revolution I love You is the second part of a trilogy that intends to explore the political and theoretical implications of the concept of ‘revolution’, with a certain commemorative concern. It was preceded by Revolution is not a garden party, another international exhibition that focused on the centrality of the 1956 Hungarian Uprising for the evolution of artistic and political practices in the communist realm as well as it’s significance for later revolutionary practices. In the exhibition catalogue that marked the 50th anniversary of the 1956 Uprising, the curators concluded that ‘the truth about revolution is part of a contested history, a living process of rewriting and interpretation in which art takes a decisive part’. [vi]

Naturally, it was the 1968 anniversary that enriched this quest for revolution’s truthfulness. Revolution I Love you, entitled after a forgotten ’68 slogan that can be easily googled, seeks to continue the aforementioned meditation on the concept of revolution by focusing this time on the ‘translocal’ and articulative character of the events. Thus, the interest lies on the intersections of art, theory and politics that reshaped the cultural and artistic field, in a comparative all-European spirit. The narration unfolds in three, interconnected chronological perspectives, as it incorporates artifacts produced in the immediate aftermath of the '68 events in Eastern Europe, namely in Poland and Czechoslovakia, and includes more recent and current approaches to contemporary sociopolitical events. [vii]

Tamás St. Auby’s and Zofia Kulik’s fluxus-like Czechoslovak Radio 1968 and Shades of Red, 1971, are selected as examples of critical political art within the boundaries of the communist regime. Auby’s sulphur-covered brick-radio and Kwiek-kulik’s slide show of several artistic actions based on the presence of the ‘colour red’ in different contexts, put forth ideas of resistance and dissent within the communist framework, both in political and aesthetic forms. Furthermore, in the case of Kulik and her artistic ‘double’, Przemyslaw Kwiek, this attempt was in alignment with the Polish soc art movement, a radical attempt to form a new avant-garde that would productively use novel artistic languages against the dominant paradigm of socialist realism, while striving at the same time to find new ways of linking the aesthetic and the political. Their quest for urgency in both political and artistic terms centered upon the creation of spectacles and took on symbolic and formal rituals, creating what could be referred to as a local institutional critique. [viii]

Moving towards more contemporary interventions, works like Mladen Stilinovic’s Marx’s pseudo-quotation on work installation (Work is a disease, 1981) and Jeanne-Baptiste Ganne’s Specchio, 2007, discuss the figure of the artist as a producer while centering on the frequently discussed issue of labour, with its complex timely connotations. Another major concern revolves around the theme of contemporary protests, as it is manifested through the works of Nancy Davenport (MayDay and What Do We Want, 2001), Olivier Ressler and Zanny Begg (Globalizing Protest and What would it mean to Win, 2004–08). Whether footage from May Day celebrations and protests is video looped and used as a screen saver (Davenport), or whether photographs and video footage from recent G8 protests is collected and presented as documentation (Ressler & Begg), what remains is a certain uneasiness and tension when one is confronted with the need to comment on the contemporary political and social movements.

Some other interesting works that cover a certain reflection both on the artistic media themselves and on the sociopolitical context of the ’60s can been seen as linked to ideas of communication, participation, experience and relation, words that have come to the epicenter of the current artistic discourse. This can be seen in Stefanos Tsivopoulos’s video Remake, 2007, a poetic, reflective meditation on the birth of public television discourse in a repressive era. On the other hand, installations such as Miklos Erhardt’s The Society of Spectacle, 2004–07, utterly miss the critical edge as they remain trapped in a naïve, relational pseudo-communicative celebration of (a) common experience.

There is much someone could argue with regarding the neat, orderly ex-position, from the absence of works that comment on the truly global character of the ’68 movement moving beyond an East/West ‘European’ divide, to the absence of any speculation on the very idea of artistic commemoration … But my intention, as a political theorist and historian who takes an interest in contemporary art, is to focus, in the remaining paragraphs, on the connection between art and politics in our contemporary artistic practice — an attempt that quite often entails a reflection on history, memory and identity.

It is true that in our globalised world of wild capitalist exploitation and free market domination, the world of art has adapted in a remarkable way, as it is manifested by the rising power of institutions, corporate collectors, blockbuster exhibitions, celebrity artists, among others … It is also true that today we are experiencing a rapid and, at times, unprecedented radicalisation of artistic practice. This apparent antithesis has led many critics to locate an antinomy in contemporary artistic discourse. Whether it is an antinomy, a paradox or a perverse kind of dialectic, what remains undisputed is that this overt/hyper politicisation of contemporary art frequently disgorges into apolitical apathy, which is in accordance with our dominant post-democratic ethos.

What is at stake here is the recognition of the constitutive antagonistic element that is rooted deeply in our contemporary societies and constitutes the sociopolitical field. This realisation can indeed lead to a new conception of the multiple intersections between art, politics and history as collective memory and identification, and energise a reflective critical stance that on the one hand does not evaporate the artistic field to a transparent immediacy, and on the other hand does not affirm the current apolitical doxa. [ix] But this is another, more complicated story that has nothing much to do with the love of the ‘revolution’ …

[i] One can examine discussions as diverse as What’s left of May ’68 (http://www.cohn-bendit.de/dcb2006/fe/pub/en/dct/474) and Contemporary art shows since ’68 (http://www.tate.org.uk/modern/eventseducation/symposia/15962.htm)

[ii] http://www.historein.gr/index_en.htm

[iii] http://www.avgi.gr/NavigateActiongo.action?articleID=402876

[iv] http://www.greekstatemuseum.com/kmst/exhibitions/article/69.html

[v] http://www.trafo.hu, http://www.internationalprojectspace.org/aboutips.htm

[vi] http://www.translocal.org/shows/index.htm

[vii] http://www.translocal.org/revolutioniloveyou/index.html

[viii] Lukasz Rondula, ‘SocArt: Redefining the Relationship Between Art and Politics’, in Maja & Reuben Fowkes (ed.), Revolution I love You, Budapest, 2008, pp. 129–133. See also http://www.polishculture-nyc.org/polish_socialist.htm.

[ix] This issue, the very basic elements of which I tried very briefly to sketch, has been introduced in the Greek context by Yiannis Stavrakakis and Kostis Stafylakis both in their article on the ‘Fundamental Paradoxes of Contemporary Art in the Age of Blockbuster Exhibitions and the Metapolitcal’, The Athens Contemporary Art Review, vol. 10, June 2007 (http://www.athensartreview.org/ENbissues.htm) and in the recent anthology that they edited in Greek, entitled Το Πολιτικό στη Σύγχρονη Τέχνη [The Political in Contemporary Art], Εκκρεμές, Αθήνα, 2008.