Richard Prince

Reviewed by Evi Baniotopoulou

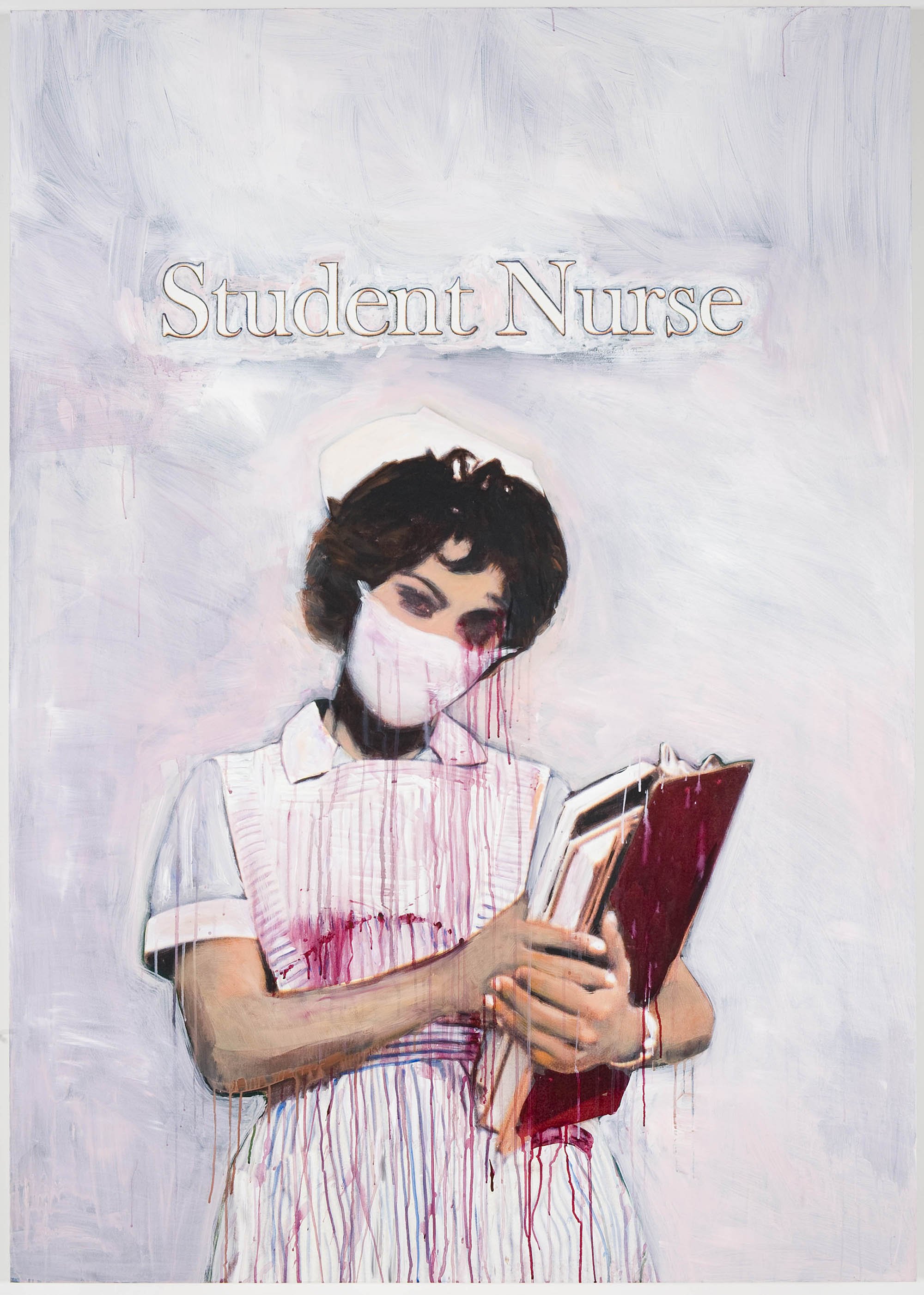

Richard Prince, Student Nurse, 2005, acrylic and inkjet on canvas, 193 × 137.2 cm

The recent Richard Prince exhibition at London’s Serpentine Gallery was one of many ambitions. Preserving, on the one hand, the gallery’s long-established, and favoured by its current directors, practice of the monographic, frequently retrospective, presentation of a celebrated artists’ work, the exhibition also set out to fulfil a number of other aims: to be as comprehensive as possible an overview of Prince’s work, as the first major presentation of his art in the UK, and as such tackle the expectations and projected reactions of a predominantly European audience to the quintessentially America-oriented artist’s work; to provide, as the third and final stop of an exhibition tour, a convincing and respectful scaled-down version of the two preceding, large retrospective shows of the artist’s work at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum and the Walker Art Centre; [i] to maximise the potential of the gallery building’s ‘domestic scale’; [ii] and to allow the artist to select and install the works on display, mirroring ‘the installation of [his] work in his own buildings’. [iii]

Strictly considering the projected aims of an ‘overview’ exhibition, this was not a bad one. The visitor was treated to a necessarily constrained in number, owing to a combination of the gallery’s limited space and some of Prince’s outsized recent sculptures, but cherry-picked 31 works, spanning the iconic artist’s 30-year long career and showcasing his interest in and mastery of a variety of media. From his relatively early series of Ektacolor photographs of men and women ‘looking in the same direction’ (Untitled [three women looking in the same direction], 1980), his series of female, semi-naked bikers (Live Free or Die [gang], 1986), and the now-iconic, 1989-appropriated Marlboro ad Untitled (Cowboy) from his Cowboys series; through to his mid-and late-’90s photographs from Upstate New York [iv] and the seemingly faded and re-written ‘jokes’ large canvases; [v] to examples of more recent works, including his ‘Hoods’ [vi] (Continuation, Hum Bomb and The Sound from 2004–05 and more recent ones such as Trips, Gomper and No milk or butter since my cow left home from 2007–08), his ‘Nurses’ [vii] (the paintings Nurse on Trial, 2005 and Surf Safari Nurse, 2007–08), his ‘illustrations-cum-book cover’, both entitled Untitled (original), 2007, his ‘check paintings’ (Untitled [portrait], 2007–08), his objet-trouvé-based furniture (Untitled [backboard], 2008), his ‘tire planters’ (Untitled [tire planter], 2008), his vinyl-wrapped Buick (Covering Hannah [1987 Grand National], 2008), his album covers-cum-drumhead (Untitled [original], 2008] and his just finished series of paintings of men superimposed on Willem de Kooning’s women (all three Untitled [de Kooning], 2008) [viii], the exhibition was equally a good introduction to Prince’s work for the uninitiated and a powerful injection for a Prince-loving audience.

The focus, however, was both by means of quantity and of installation, on the more recent works, while some absences of important works were noted. Spiritual America, the work showing a pre-pubescent, naked and lubricated 10-year old Brooke Shields seemingly emerging from a steam bath, which marked Prince’s shot to fame in 1983 when he photographed it and hung it at the front of his shop, and also lent its title to the two American shows this year was notably absent, as was any example of his cartoon works. [ix] The avid collector’s activity and objects, almost entirely absent from the actual exhibition space, were very cleverly covered in the form of an early, reprinted Prince text in the artist book that was produced in conjunction with the Serpentine exhibition. [x] More recent works and media beyond photography, were definitely privileged: the exhibition started with an enveloping installation of Hoods, ‘guarded’ on either side by symmetrically positioned Nurses paintings, while his large paintings took centre stage in the central room of the gallery, elevated to objects of high importance if not by this centrality itself, then certainly by the fact that they shared the same space as the quintessential cowboy photograph. This approach was definitely in line with the Guggenheim’s aspiration to eschew a chronological or medium based presentation, favouring instead thematic and formal comparisons, an approach also devised by the museum in order to avoid the replication of previous interpretations of Prince’s work as critical of Postmodernism. [xi] Perhaps, however, this is also a reflection of the artist’s belief about how a European audience would receive his art. As Prince explained to the Serpentine Co-Director Hans Ulrich Obrist in his interview for the artist book produced by the Serpentine on the occasion of the exhibition, his phrase “It’s all about this idea of America” from an interview a year ago referred to a concrete, ‘real’ experience of America through ‘television, movies, magazines’ — and that Prince had always thought that “a European audience would think it’s abstract”. [xii] It is almost as if Prince is here lending a sort of a helping hand to the ‘European audience’ [xiii], who would expect something abstract. Car hoods are the closest one can get to abstraction, and even a universal quality with Prince’s work — and if that position were to be stretched further, one could even argue that the Hoods could also be seen as a sculptural rendition of abstract expressionist paintings. It is in that sense that the exhibition is rather structured as an ‘idea of America moving from the outside in’, from the more generic, universally applied, to the more specific — from the Hoods, the and Willem de Kooning to the tire planters, the American women, the cowboy, the jokes, the car and the backboard, to come perhaps full circle to abstraction.

A career-spanning selection of works aside, the exhibition’s other main aim, namely to mirror the artist’s installations in his own buildings is the point that is potentially the most interesting in that otherwise rather sterile exhibition. At a first glance one could reach the over-simplifying conclusion that this aim failed miserably. The canonical, symmetrical and — despite the best intentions to create meaningful dialogues between the works- lacking in pulse representation of Prince’s work in the pristine, white cube-turned rooms of a quintessentially traditional English building did not manage to convey the inspiring, place-bound, sometimes seemingly dusty and abandoned but nevertheless conceptually and space wise coherent and gripping installations in his studio buildings, as these become manifest from documentary photographs and visitors’ witnessing. [xiv] But this exhibition, in stark contrast with the other two American shows, is called singularly Continuation, which suggests ‘nothing old, nothing new … a way to connect the past and still be in the present’. [xv] One cannot help but think that the Serpentine Gallery show gave Prince the excellent opportunity to expand his artistic experimentation to the medium of exhibition making, thus ‘continuing’ in London what already exists (and actually recently gained ‘artwork’ status through its purchase by the Guggenheim museum) [xvi] in his studios in the States. Installing his own collection outside his own buildings, in the surroundings of a London mainstream gallery must have doubtless been for Prince a unique challenge in precisely this manner.

Alternatively, the game may well have been played on a purely curatorial orientation level. The exhibition, itself a zoomed in, rid of the unnecessary ornaments of the large retrospective — great number of works, textual interpretation-product can also be seen as a curatorial transference (or, indeed, appropriation ‘à la Prince’), as a nod to the artist’s own practice, a subtle interpretation of the artist’s work through exhibitionary deliberation and final delivery.

[i] Richard Prince: Spiritual America, shown at the Solomon R.Guggenheim Museum (28 September 2007 – 9 January 2008) and the Walker Art Centre (22March – 14 September 2008).

[ii] Housed in a 1934 building that originally served as a tea pavilion, the Serpentine Gallery has often been for its domestic scale, which inspires more contained exhibitions and intimate representations than the average art institution space.

[iii] This was an intention clearly stated in the exhibition’s accompanying literature, where Continuation was described as “a uniquely personal exhibition of the artist’s work, selected to create an environment reflecting the Gallery’s scale and location. Prince is a voracious collector of art, furniture, memorabilia and books, which he houses in a variety of buildings alongside his own artworks. The exhibition will represent a direct dialogue with these spaces, mirroring the installation of his work in his studios and home.’ Press Release, Richard Prince: Continuation at the Serpentine Gallery.

[iv] Prince moved to Upstate New York in 1996.

[v] These represent the distillation of this phase of his turn to painting in 1987.

[vi] Hoods are fibreglass car hoods, used as ‘replacement parts’ while the original, destroyed hoods are being fixed. These have been made into wall sculptures or floor sculptures placed on bases of plywood or wood by Prince.

[vii] The iconography for Prince’s Nurses paintings is based on nurses adorning the covers of romantic novels that the artist has collected.

[viii] A series Prince conceived when he started drawing directly on a catalogue of De Kooning’s work, see America Goes to War … , op. cit.

[ix] For the importance of his cartoon works see Nancy Spector, ‘Nowhere Man’, in Nancy Spector, Richard Prince: Spiritual America, Guggenheim Museum, New York, 2007, p. 36.

[x] Richard Prince, ‘Bringing It All Back Home’ (first published in Art in America, issue 76, September 1988, pp. 29–33], in Richard Prince: America Goes to War … Swimming in the Afternoon (exhibition curated by Julia Peyton-Jones, Hans Ulrich Obrist and Kathryn Rattee), Koenig Books, London, 2008.

[xi] See Lisa Dennison, Preface, in Spector, Richard Prince: Spiritual America.

[xii] Richard Prince, ‘America Goes to War … Swimming in the Afternoon … ’, in America Goes to War … , op. cit.

[xiii] Quite why Hans Ulrich Obrist insisted on the notion of a European audience referring to the audience of an essentially multicultural city is an issue that merits a separate discussion — it however does highlight further Prince’s exclusive concern with America.

[xiv] As can be seen in the book Second House, there is no sense of order in the arrangement of the artworks. The only thing that is similar to the Serpentine exhibition is the ‘hoods’ hung on the walls, which Prince explained was done because they are the only artworks that can withstand the temperature fluctuations in the unheated in the winter house. However, the painted white but still unfinished walls of his studio installations, and his strong dialoguing connections made among his works in his studio buildings are not felt in his Serpentine show. Perhaps Prince chose to do here what he explains to have done with the Guggenheim show: ‘Things ended up on the walls because they looked good there. The whole thing was laid out as if the museum was a magazine’ (‘America Goes to War’, in America Goes to War, op. cit.). See also Jack Bankowsky, ‘Ciao Rensselaerville’, in Spiritual America, op. cit., pp. 334–348 for a comprehensive history and analysis of Prince’s out-of-gallery showing activity.

[xv] Prince in America Goes to War, op. cit.

[xvi] The Guggenheim Museum acquired Richard Prince’s Second House, including the building, its surrounding land and contents of the building, with the sole exception of the Hoods, purchased by collectors under the condition that they would eventually gift them to the Guggenheim and occasionally make them available for a reconstitution of the original installation.