The Archive of Destruction

Pedro Lagoa interviewed by Christopher Marinos

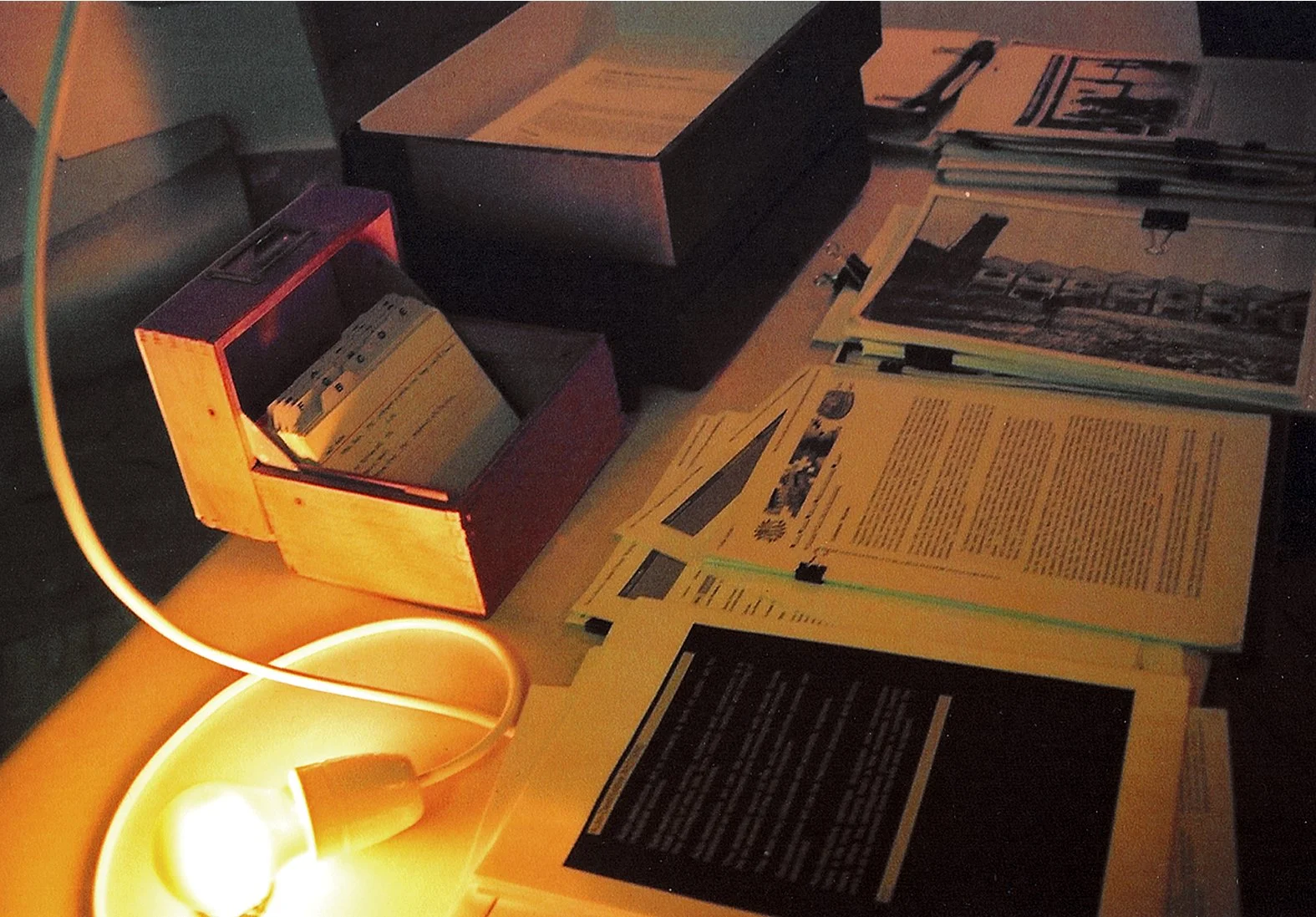

⁰¹⁻⁰² Archive of Destruction: The Quagmire Fields Section, installation view, Quagmire Fields, Tschoperl, Frankfurt am Main, 2007

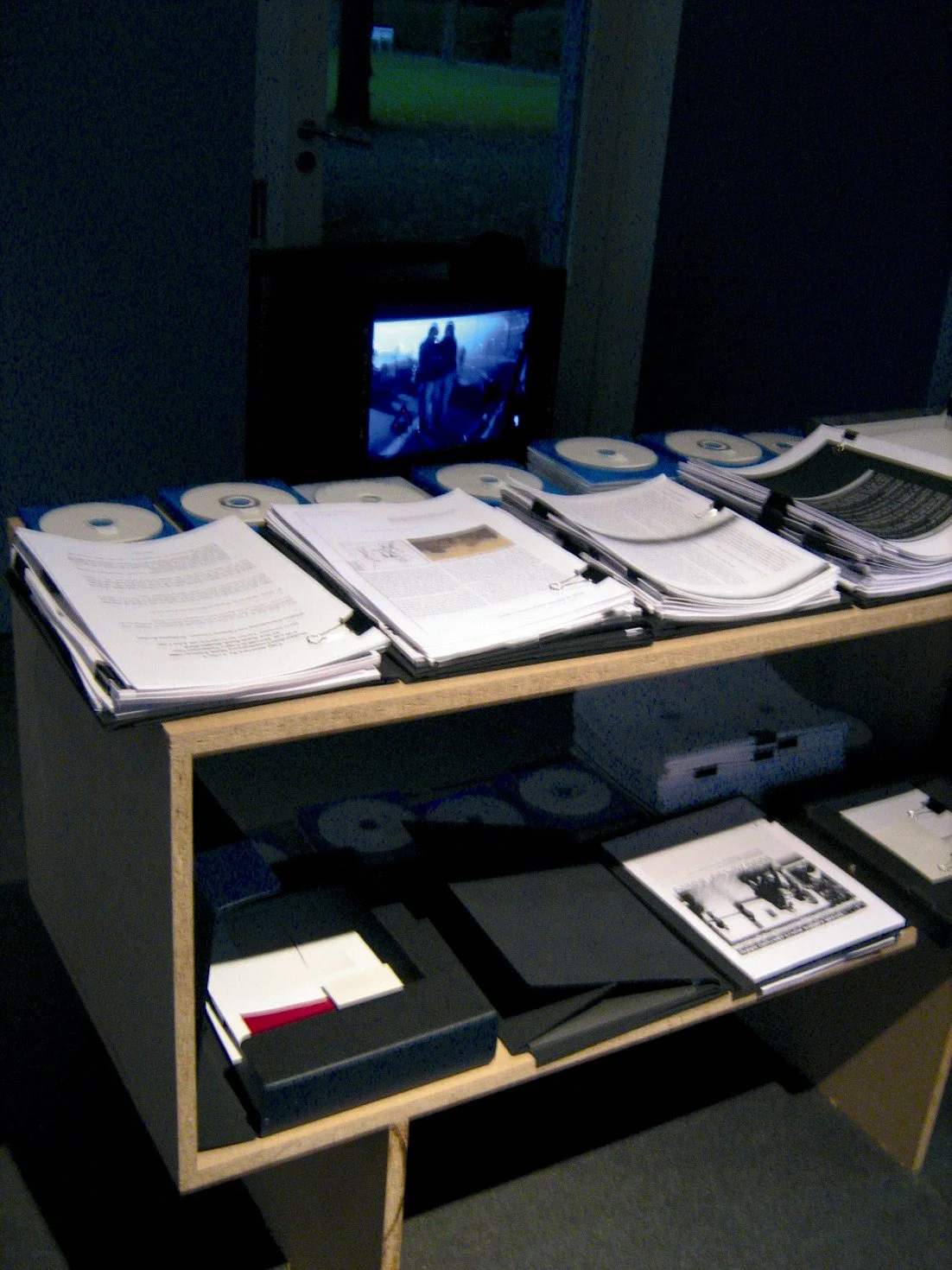

⁰³⁻⁰⁴ Archive of Destruction; installation view, Ende, Städelmuseum, Frankfurt am Main, 2008

⁰⁵ [a cut through the] Archive of Destruction (video stills), 2007–08, video, colour, sound, 62 min. Exhibited at I Will Not Throw Rocks, FormContent, London, 2007; Ende, Städelmuseum, Frankfurt am Main, 2008.

Christopher Marinos: Can you briefly explain what the Archive on Destruction consists of? When (and why) did you start collecting the material?

Pedro Lagoa: To put it briefly, the Archive of Destruction is an ongoing project of a personal archive dedicated to destruction directed towards physical objects and towards ideas. As destruction directed towards objects is understood the physical/material side of destruction, while the destruction towards ideas focuses on more abstract/immaterial practices of attempted destruction of established ideological systems, codes, practices, theories, etc. The Archive had its start in mid-2007, and the idea came in the context of an invitation by curator Caterina Riva to take part in an exhibition dealing with the subject of Academia and SchoolAs destruction had been a long time interest for me and was already present in some previous projects, I thought the appropriation of an academic structure, as the archive, to collect documents on actions and thoughts that were close to me and represent, somehow, a denial of the archive’s function — preservation of memory and erasure of memory — could be an interesting direction to explore, and one that would be able to continue developing after that particular context of the exhibition. Another interesting aspect for me was that it would allow me to organise and re-contextualise material that I had been gathering before without any specific purpose other than personal interest. Hence, the first references and additions to the archive were found among my collection of books, records, videos and so on, constituting the starting point for further research.

CM: Therefore, unlike the typical detachment and stiffness associated with documentation strategies, there’s an ‘emotional’ value attached to your archive. Is there a critical aspect to be found in the way your project is operating? Exactly how do you think to present it in the future?

PL: Being an archive on destruction, I thought the only consistent way of operating it would be to try as far as possible to organise it in accordance to its subject. Thus, in the process of definition of the way the archive operates, I’ve been trying to avoid, or go somehow against some ways and procedures with which most institutional archives operate. The decision to assume the archive as personal and subjective allows me a bigger freedom in the criteria I use for selecting the documents to add to the archive and the ways of presenting them, when compared with institutions or others who are bound to different sorts of objective rules and constraints. In this sense, and as an example, the archive has been changing content and rules of organisation according to the context of presentation. There are no hierarchies or impositions of rigid classifications or categorisations on the documents, these being presented with an order, which is always different, but without making it explicit.

PL: Nevertheless, this has its limitations, and at the moment I think the possibilities of expansion for the archive will go through the development of ramifications, that will not be dedicated to archival functions but will explore possibilities of working the archive’s material and ideas into new forms. I have already started to work and experiment with some possibilities, but they’re still at a very early stage, for the moment.

CM: In her text The Archive in the Present: for a genealogy of the slightest traces, published on the occasion of Documenta X, 1997, Italian philosopher Judith Revel concludes that: ‘if our present, through a curious temporal twist, is only legible on the basis of the past, on the basis of what we are no longer, then the archives transformed the distanced echo of anonymous voices into a critical instrument for today: their history is the very mark of our experience, and their genealogy is the necessary path to a critical ontology of actuality’. This Foucaultian conception of the archive tempts me to ask you: What the Archive on Destruction can tell us about the present?

PL: I’m not sure I have a precise answer to that … I believe that everything of what is in the archive keeps for sure a strong and pertinent relationship with our present, the ideas and practices there documented can be easily found nowadays. But the articulation of the present with the archive, or what the archive may be able to say is, in my view, much dependent on how one subjectively perceives the present and then relates it with this particular line of history that the archive presents through its selection of documents. One other aspect of this archive of destruction’s relation with time, especially with the present, is its complex and somewhat paradoxical relation. I suppose one of the main ideas that come across the content found in the archive can be said to be one of refusal. Destruction as refusal to accept, to conform, to change, to comply … and one can maybe speculate that they were also refusals of time. When a riot or revolution took place, when Schönberg broke with tonality, when John Latham chewed Clement Greenberg’s Art and Culture, or when the Luddites broke mechanised looms, for example, they were actually producing actions of refusal of their political, cultural or social present. And these actions, I think, with a more symbolic level or a greater affect on reality can be regarded also as actions against their present, against the time that generated them.

CM: Does your archive also include real events such as riots or revolutionary actions of social change? For instance, what was your reaction to the recent rioting — described as ‘an orgy of destruction’ — that swept Athens and many parts of Greece? Did you start collecting press clippings and videos from the web?

PL: Yes, of course, they constitute an important part of the archive. They represent attempts at destroying an established social or political situation, operating on both an abstract and a material level. The ‘orgy of destruction’, as it was called, definitely captured my attention — as well as some other riots that took place in recent years, like Paris, for example — therefore I was for some time following the development and collecting images and some news clips on the web, having in mind a possible inclusion in the archive.

CM: Speaking of Athens and catastrophe, I’d like to bring to your attention two Greek texts which proclaim the destruction of the Parthenon and rightly deserve a place in your archive. The first is a poem (Acropolis) that belongs to art critic and poet Nicolas Calas (1907–88) and the other is a manifesto (Proclamation) written in 1944 by peripatetic philosopher Giorgos Makris (1923–68), a highly influential figure in the Athenian art world of the ’60s. This leads to my next question: in terms of thoroughness, where does your research begin and end?

PL: Thank you for the references, I actually didn’t know them. I think the immediate conclusion is that the destruction of Athens — and the Parthenon by the way — conveys a highly symbolical reading, as Athens is regarded as the birth place of western civilisation and democracy. If one is to analyse the idea of destruction of Athens, from the present political situation, for sure some lines can be established between this symbolic destruction and the riots that transpire an ill feeling (‘malaise’) or refusal towards a political, social and economic model that shows signs of apparent exhaustion. On the research, the archive is an open project, without a planned end, and so is the research: a continuous open process. The beginning of the research may stem from associations with material already in the archive, by suggestions or chance encounters. I continuously gather information or documents, but as I don’t work exclusively on this project, only after some time I devote time to organise, select and further the research on the gathered topics or events. This leads to a somehow non-linear research, where each document collected usually leads me to a few more — which are not necessarily restricted to that initial subject — which will in their turn once again lead to a few more, and so on. Though there are subjects to which I dedicate more attention at certain times, until now I don’t think I can say that I have reached the end of my research on a specific topic of the archive. It’s still an open process.

CM: Perhaps, in your case, the ultimate act of destruction is that of the archive itself. I can’t think of a more appropriate and ‘better’ ending to your archive than that of its total annihilation in some way — only then we would have a true auto-destructive art, as Gustav Metzger liked to call it. Don’t you agree?

PL: I can’t say I have given much thought to that as I see the archive more in its initial steps than close to its end. For the moment, I tend to agree with you, that the archive will have to be somehow destroyed or destroy itself, at a certain point, to make complete sense, and somehow to close the circle. What I’m not so sure about is how that could be done in a way that is fitting accordingly, without becoming too literal or falling into redundancy within its concept. This is, if the archive should be physically destroyed, or if it would be more interesting that the destruction should be approached on a more subtle and abstract level.

CM: Since your archive also contains immaterial works and ideas (from films to manifestos), it would be misleading to talk of a sheer physical destruction. The archive can be destroyed only symbolically, as an act of personal catharsis. Thus, unavoidably, reflecting on the destruction of an archive on destruction we are caught in a vicious circle, and obliged to discuss the (conceptual) role of the work of art. Maybe we should stick to more basic issues: Are there any favourite works on destruction, from those you’ve collected so far?

PL: Being, as you mentioned previously, an archive with an ‘emotional value’, there are some works with which I do have a special relationship. There are of course some names that are more obvious as an influence, such as Duchamp, Debord, Dadaists, Daniel Buren or John Cage, which I particularly like for the whole of their works and were rather influential in the idea of starting the archive, but I’ll mention just a few other individual works that I’m particularly fond of. One of them is this book, Heliogabalus or the Crowned Anarchist by Antonin Artaud, which is a beautifully written book on the life of the Roman emperor of the same name, who in four years subverted the whole political and religious system of the Roman Empire in the most outrageous ways. Still in literature, what Louis-Ferdinand Céline did with French language, at most levels, in Mort à Crédit is rather admirable, as he completely destroyed the French academic writing style with that book. From the Cloud to the Resistance, is a film by Jean-Marie Straub and Danièle Huillet, where the beauty of the shots comes as much from the image as from the text, with their very own way of using — or creating — time in film; divided in chapters, it is a reflection on the creation of gods, or authority and the almost immediate resistance and rebellion of men against them. Other than that their film is stripped bare of any sort of spectacular tricks: ‘It’s needed that a film destroys at each minute, at each second, what he was saying in the preceding minute, because we are suffocating under clichés and it’s needed to help people to destroy them’, Straub once said about their own process. Albert Cossery, an apparently not so well-known Egyptian writer, who in about 60 years of writing published only eight books because he refused to write more than a line per day. His book Les Fainéants Dans la Vallée Fertile, is surely one of the best praises of laziness ever written and a nice attack on traditional values or notions of ambition, productivity and achievement.

And to finish, there’s one work of Gustav Metzger, to whom you referred above, that I’m particularly fond of, which is the Art Strike, with its almost quixotic idealism. In this work he proposed that all artists of the world stop producing art for three years in order to destroy the art system and create better conditions for them.

Pedro Lagoa is an artist who lives and works in Frankfurt.